Petri Dish 2.0: How Open Culture is Automating the Future of Cell Science

By Chrissa Olson.

Biology is messy. From one culture to the next, it’s hard to get cells to behave in the same way. And this is even more true for organoids, small spheres of 3D tissue that scientists grow and use to study organ function. It’s hard to confirm discoveries if you can’t get the same results twice. But what if you could?

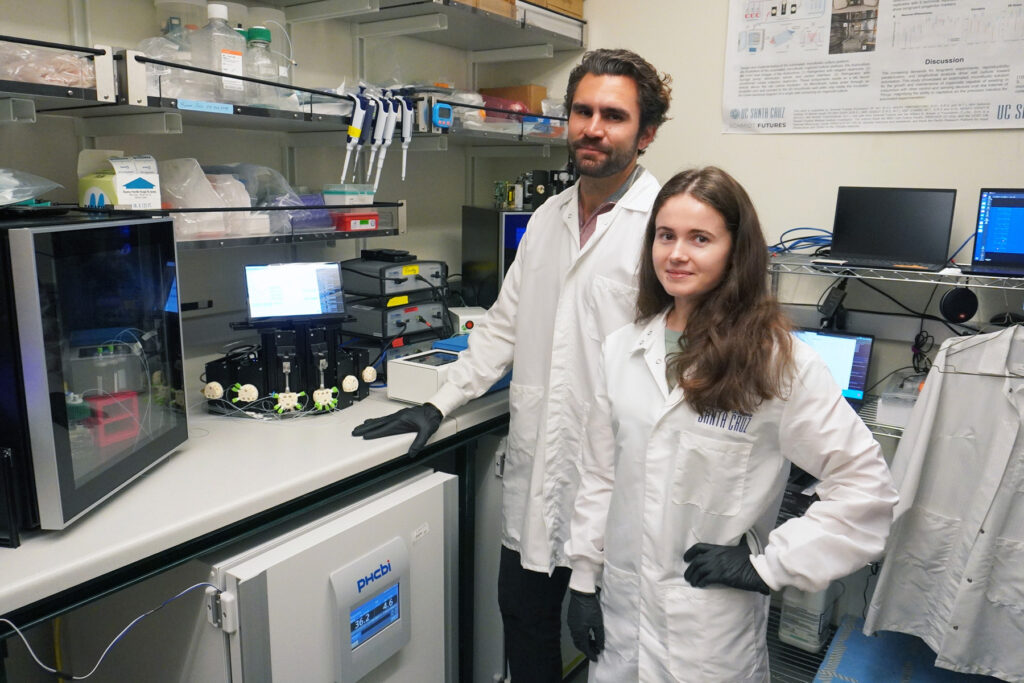

At Open Culture, the UC Santa Cruz postdoc team of Kateryna “Kate” Voitiuk and Spencer Seiler is making it easier not just to grow organoids in culture, but to do so in an automated system that creates consistency, reduces human errors, and works while you sleep. Their specialization: brain organoids.

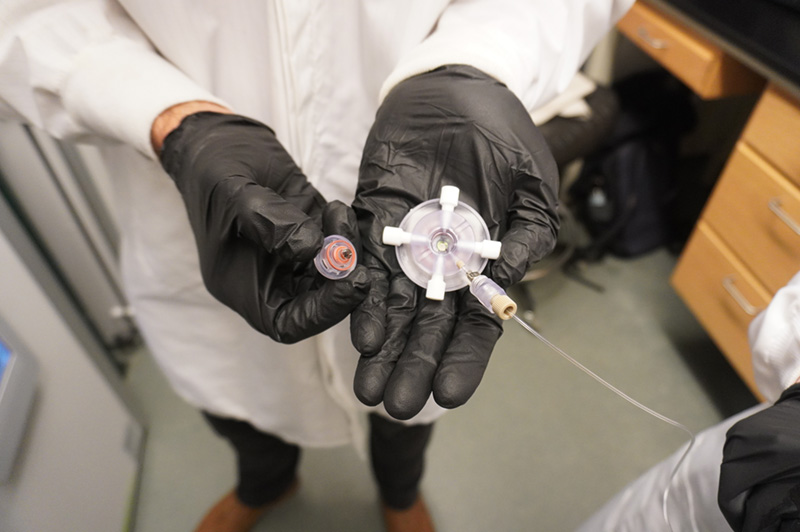

Dubbed the “Autoculture” in their first publication in Nature Scientific Reports, their system will make it possible to grow and study large numbers of organoids that have increased health and behave consistently from one batch to the next no matter where you are. Then, researchers can use organoids as models of the human brain in the search for urgently needed medicines to treat diseases like epilepsy, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s.

“[Growing organoids at the moment] is a little bit like baking cookies,” Spencer says. “Right now, the chef is accidentally burning some batches, and sometimes they add a little too much extra flour, so the end result is cookies, but they’re all different. The better tactic is to get the really great recipe down, and then have a machine do it every time the same.”

According to Kate, several platforms are already doing microfluidic media exchanges or cell cultures under flow – but what differentiates Open Culture is their software.

They want their machine to be as intuitive as an iPhone – where from the moment you unbox it, you don’t need a user manual. By feeding the machine’s protocols to a large language model, then hooking it up to messaging platforms like Slack, they hope customers will be able to talk to and collaborate with the machine as if it were a research assistant.

“You just come into your lab with whatever project you have with the ability to say, ‘How did it run last night?’” Spencer says. “You can talk to your experiment. We’re increasing accessibility through interaction.”

“We want to make every biologist feel like they’re Tony Stark,” Kate says, to replicate Iron Man’s robot AI assistant that responds impeccably to voice command.

It’s obvious from even the way they talk that they propel each other forward. Their colleagues call the duo “the rocketship.” Spencer describes Kate as an engineer who can take a concept and 3D print it into a contraption by the next day, and Kate says Spencer matches her energy.

Together, they move fast – and they want to take the science of cell culture with them.

As one of the newest additions to the QB3 Early-Stage Mentoring program, they’ll be working with Widya Mulyasasmita, a QB3 mentor and a general partner at BEVC, a Berkeley- and Bakar Labs-affiliated investment firm.

“We’ve been encouraged through QB3 mentorship to dream bigger,” Spencer says. “It’s not exclusive to neural space, or cell culture space.”

As members of UCSC’s “Braingeneers” group, Kate and Spencer also participate in QB3’s Collaborative Research program, investigating the genetic origins of autism in work funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Their cell culture system will make this kind of multi-campus work more efficient.

“For example, at UC Berkeley, they have a really amazing imaging system,” Spencer says. “And at UC Santa Cruz, we have these high-density electrical recording systems that can display all the fireworks of the neuronal activity. If we can generate the same tissue and agree in both places using this machine, then we can each do our downstream analysis.”

Open Culture was founded in July 2024, and they raised $50,000 from UCSC’s Innovations Catalyst Grant to further develop IP and another $50,000 from the U.S. National Science Foundation Innovation Corps.

The company’s name came serendipitously – one hour before the deadline for a small, internal university grant, they decided to go for it and pitch their idea for a company. They had three minutes left when they reached the final question: What is the name of your company?

They had none.

Kate, having just attended the MaxWell Biosystems conference in Zurich, remembered UCSF professor Tom Nowakowski saying he liked that the conference had an “open culture.”

It popped back into her head at the last second – it was perfect. “Open” embodied both how they hoped to be a way to share information widely, and “Culture” represented the literal cell cultures. It was a “grand slam” of a name, Spencer says.

“It’s like the petri dish 2.0,” Spencer says. “A lot of biology is stuck in the 20th century, using old tactics. So what about a complete modernization to science? All of cellular biology can have an assisted tool that helps them with their culture.”